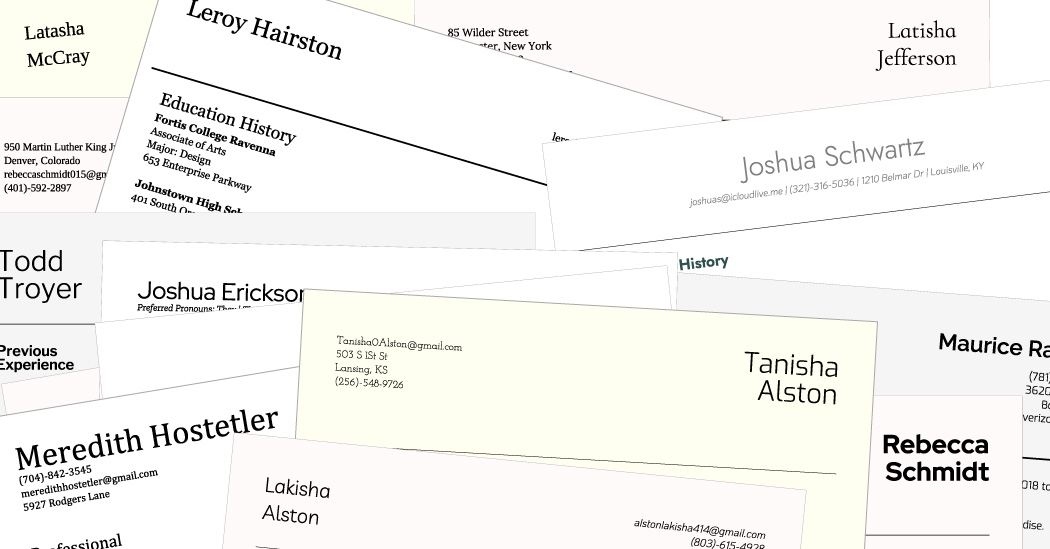

A group of economists recently conducted an experiment in about 100 of the largest companies in the country, applying for jobs using resumes created with equivalent qualifications but different personal characteristics. They changed the applicants’ names to suggest they were white or black, and male or female—Latisha or Amy, Lamar or Adam.

On Monday, they published the names of the companies. On average, they found, employers contacted purported white applicants 9.5 percent more often than purported black applicants.

However, this practice varied significantly by firm and industry. A fifth of companies—many of them retailers or car dealers—accounted for nearly half the gap in returning calls to black and white applicants.

Two companies favored white applicants over black applicants significantly more than others. They were AutoNation, a used-car retailer, which contacted supposedly white applicants 43 percent more often, and Genuine Parts Company, which sells auto parts, including under the NAPA brand, and called supposedly white candidates. white 33 percent more often.

In a statement, Heather Ross, a spokeswoman for Genuine Parts, said: “We are always evaluating our practices to ensure inclusion and breaking down barriers, and we will continue to do so.” AutoNation did not respond to a request for comment.

Known as an audit study, the experiment was the largest of its kind in the United States: Researchers sent 80,000 resumes to 10,000 job openings from 2019 to 2021. The results show how entrenched employment discrimination is in parts of the job market. of the U.S. workforce—and the extent to which black workers start behind in certain industries.

“I’m not surprised at all,” said Daiquiri Steele, an assistant professor at the University of Alabama School of Law who previously worked for the Labor Department on employment discrimination. “If you have problems with penetration, the biggest problem is the ripple effect it has. This affects your wages and the economy of your community in the future.”

Some companies showed no difference in how they treated applications from people who were assumed to be white or black. Their HR practices—and one policy in particular (more on that later)—provide guidance on how companies can avoid biased decisions in the hiring process.

The lack of racial bias was more common in some industries: grocery stores, including Kroger; food products, including Mondelez; freight and shipping, including FedEx and Ryder; and wholesalers, including Sysco and McLane Company.

“We want to draw people’s attention not only to the fact that racism is real, sexism is real, some are discriminatory, but also that it is possible to do better and that there is something to learn from those who have done a good job. ,” said Patrick Kline, an economist at the University of California, Berkeley, who conducted the study with Evan K. Rose at the University of Chicago and Christopher R. Walters at Berkeley.

The researchers first published details of their experiment in 2021, but without naming the companies. The new paper, which will be published in the American Economic Review, names the companies and explains the methodology developed to group them according to their performance, accounting for statistical noise.

The study includes 97 firms. The jobs the researchers applied for were entry-level, not requiring a college degree or significant work experience. In addition to race and gender, the researchers tested other legally protected characteristics, such as age and sexual orientation.

They sent up to 1,000 applications to each company, applying for up to 125 jobs per company in locations around the country, in an effort to detect patterns in the companies’ operations versus isolated cases. They then tracked whether the employer contacted the applicant within 30 days.

A prejudice against black names

Companies that required a lot of customer interaction, such as sales and retail, particularly in the auto sector, were more likely to show a preference for applicants who were assumed to be white. This was true even when applying for positions at those firms that did not involve customer interaction, suggesting that discriminatory practices were embedded in corporate culture or human resources practices, the researchers said.

There were exceptions, however—some of the companies that showed the least bias were retailers, such as Lowe’s and Target.

The study may underestimate the degree of discrimination against black applicants in the job market as a whole because it tested large companies, which tend to discriminate less, said Lincoln Quillian, a sociologist at Northwestern who analyzes audit studies. It did not include names intended to represent Latino or Asian applicants, but other research suggests they are also contacted less than white applicants, although they face less discrimination than black applicants.

The experiment ended in 2021, and some of the companies involved may have changed their practices since then. However, a review of all available audit studies found that discrimination against black applicants had not changed in three decades. After the Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, such discrimination was found to have disappeared among some employers, but the researchers behind the study said the effect was likely to be short-lived.

Gender, age and LGBTQ status

On average, companies did not treat male and female applicants differently. This is consistent with other research showing that gender discrimination against women is rare in entry-level jobs and begins later in the career.

However, when companies favored men (especially in manufacturing) or women (mostly in clothing stores), the bias was much greater than for race. Builders FirstSource contacted prospective male applicants more than twice as often as female applicants. Ascena, which owns brands such as Ann Taylor, reached out to women 66 percent more than men.

Neither company responded to requests for comment.

The consequences of being female varied by race. The differences were small, but being female was a small advantage for white applicants and a slight penalty for black applicants.

The researchers also tested several other legally protected characteristics with a smaller number of resumes. They found there was a small penalty for being over 40.

Overall, they found no penalty for using non-binary pronouns. Being gay, as indicated by including membership in an LGBTQ club on a resume, resulted in a slight penalty for white applicants, but benefited black applicants—although the effect was small, when it was on their resumes, the racial penalty disappeared.

Under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, discrimination is illegal even if it is unintentional. However, in the real world, it is difficult for job applicants to know why they did not hear back from a company.

“These practices are especially challenging to address because applicants often do not know if they are being discriminated against in the hiring process,” Brandalyn Bickner, a spokeswoman for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, said in a statement. (He has looked at the data and talked to researchers, though he could not use an academic study as the basis for an investigation, she said.)

What companies can do to reduce discrimination

Some common measures — such as hiring a chief diversity officer, offering diversity training or having a diverse board — were not associated with reduced entry-level hiring discrimination, the researchers found.

But one thing strongly predicted less discrimination: a centralized human resources operation.

The researchers recorded the voicemail messages the fake applicants received. When a company’s calls came from fewer individual phone numbers, suggesting they came from a central office, there tended to be less bias. When they came from individual hiring managers at local stores or warehouses, there were more. These messages often seemed rushed and informal, asking if an applicant could start the next day, for example.

“That’s when implicit bias starts,” Professor Kline said. A more formalized hiring process helps overcome that, he said: “Just thinking about things, what steps to take, having to run something by someone for approval, can be quite important in mitigating biases.”

At Sysco, a wholesale restaurant food distributor that showed no racial bias in the study, a centralized recruiting team reviews resumes and decides who to call. “Consistency in how we screen candidates, with a focus on position requirements, is key,” said Ron Phillips, Sysco’s chief human resources officer. “This reduces the chance that personal views will arise in the process.”

Another important factor is diversity among the people they hire, said Paula Hubbard, chief human resources officer at McLane Company. It procures, stores and distributes products for large chains like Walmart and showed no racial bias in the study. About 40 percent of the company’s recruiters are people of color and 60 percent are women.

Diversifying the pool of people who apply also helps, HR officials said. McLane goes to women in trucks events and puts up signs in Spanish.

So is skill-based vs. degree-based hiring. While McLane used to require a college degree for many roles, he changed that practice after determining that specific skills were more important for warehouse or driving jobs. “Now we do this for all our jobs: is a degree really required?” mrs. Hubbard said. “Why? Does it make sense? Is experience enough?”

Hilton, another company that showed no racial bias in the study, also stopped requiring degrees for many jobs in 2018.

Another factor associated with less hiring bias, the new study found, was more regulatory scrutiny — as in federal contractors, or companies with more Labor Department citations.

Finally, the most profitable companies were less biased, consistent with a long-held economic theory by Nobel laureate Gary Becker that discrimination is bad for business. Economists said this may be because more profitable companies benefit from a more diverse workforce. Or it could be an indication that they had more efficient business processes, in HR and elsewhere.

#researchers #fake #resumes #job #sites

Image Source : www.nytimes.com